It's 4am and Dr Hassan Khan, the duty doctor at Ramgarh hospital, is notified of something unusual.

The police have brought in a dead man, a man they claim not to know.

"What were the police like when they brought him in? Were they calm?" I ask him.

"Not calm," he says. "They were anxious."

"Are they usually anxious?" I ask.

"Not usually," he says, laughing nervously.

The dead man is later identified by his father as local farmer Rakbar Khan.

This was not a random murder. The story illustrates some of the social tensions bubbling away under the surface in India, and particularly in the north of the country.

And his case raises questions for the authorities - including the governing Hindu nationalist BJP party.

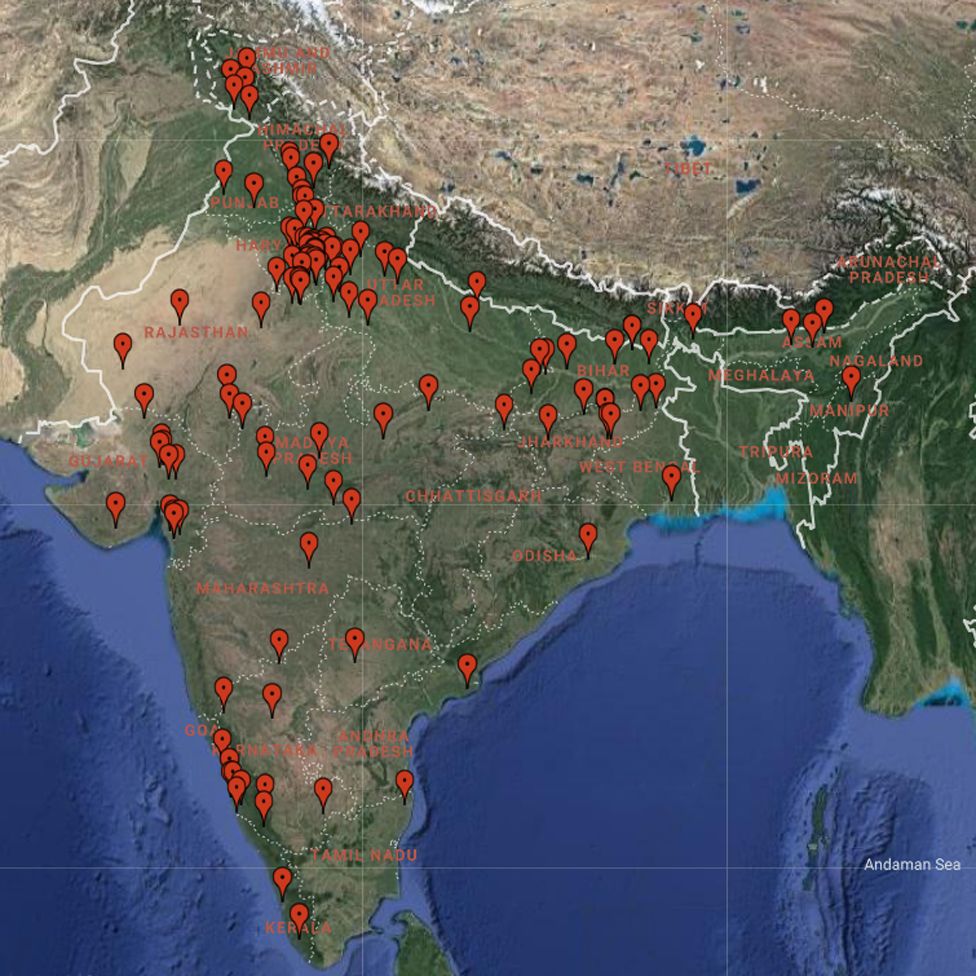

Cow-related violence - 2012-2019

He kept cows and he also happened to be a Muslim. That can be a dangerous mix in India.

"We have always reared cows, and we are dependent on their milk for our livelihood," says Rakbar's father, Suleiman.

"No-one used to say anything when you transported a cow."

That has changed. Several men have been killed in recent years while transporting cows in the mainly Muslim region of Mewat, not far from Delhi, where Rakbar lived.

"People are afraid. If we go to get a cow they will kill us. They surround our vehicle. So everyone is too scared to get these animals," says Suleiman.

Everyone I speak to in the village where the Khans live is afraid of gau rakshaks - cow protection gangs.

They believe that laws to protect cows, such as a ban on slaughtering the animals, are not being fully enforced - and they hunt for "cow smugglers", who they believe are taking cows to be killed for meat.

Often armed, they have been responsible for dozens of attacks on farmers in India over the last five years, according to data analysis organisation IndiaSpend, which monitors reports of hate crimes in the media.

On 21 July 2018, Rakbar Khan met the local gau rakshak.

There are some things we know for certain about what happened that night.

Rakbar was walking down a small road with two cows. It was late and it was raining heavily.

Then, out of the dark, came the lights of motorbikes. We know this, because Rakbar was with a friend, who survived.

The gang managed to catch Rakbar, but his friend, Aslam, slipped away. He lay on the ground, in the mud and prayed he wouldn't be found.

"There was so much fear inside me, my heart was hurting," he says.

"From there I heard the screams. They were beating him. There wasn't a single part of his body that wasn't broken. He was beaten very badly."

Aslam says that Rakbar was killed then and there.

But there is evidence that suggests otherwise.

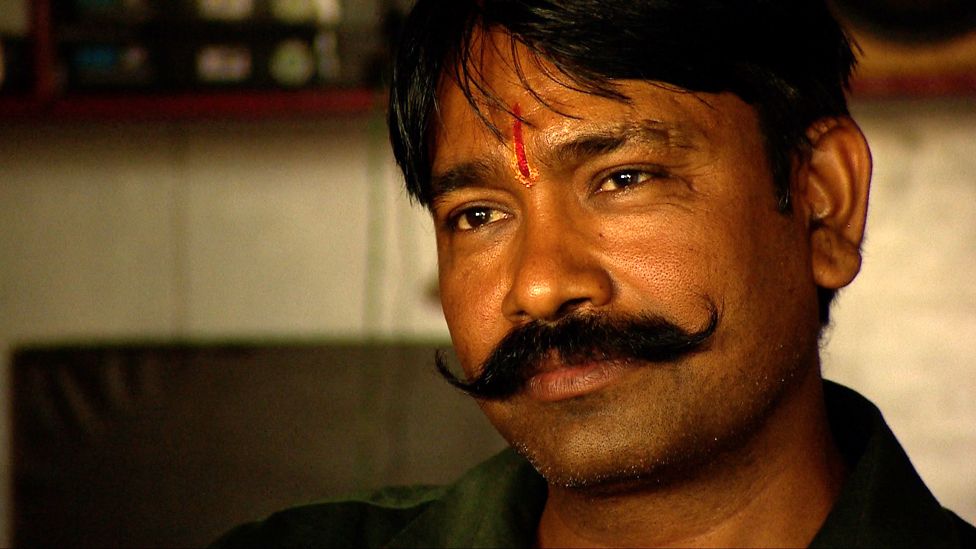

Much of what happened next focuses around the leader of the local cow vigilante group, Nawal Kishore Sharma.

Aslam claims he heard the gang address him by name that night, but when I speak to Sharma, he denies he was there at all.

According to Nawal Kishore Sharma, he then drove with the police to the spot. "He was alive and he was fine," he says.

But that's not what the police say.

In their "first incident report" they say that Rakbar was indeed alive when they found him.

"Nawal Kishore Sharma informed the police at about 00:41 that some men were smuggling two cows on foot," the report says.

"Then the police met Nawal Kishore outside the police station and they all went to the location.

"There was a man who was injured and covered in mud.

"He told the police his name, his father's name, his age (28) and the village he was from.

"And as he finished these sentences, he almost immediately passed out. Then he was put in the police vehicle and they left for Ramgarh.

"Then the police reached Ramgarh with Rakbar where the available doctor declared him dead."

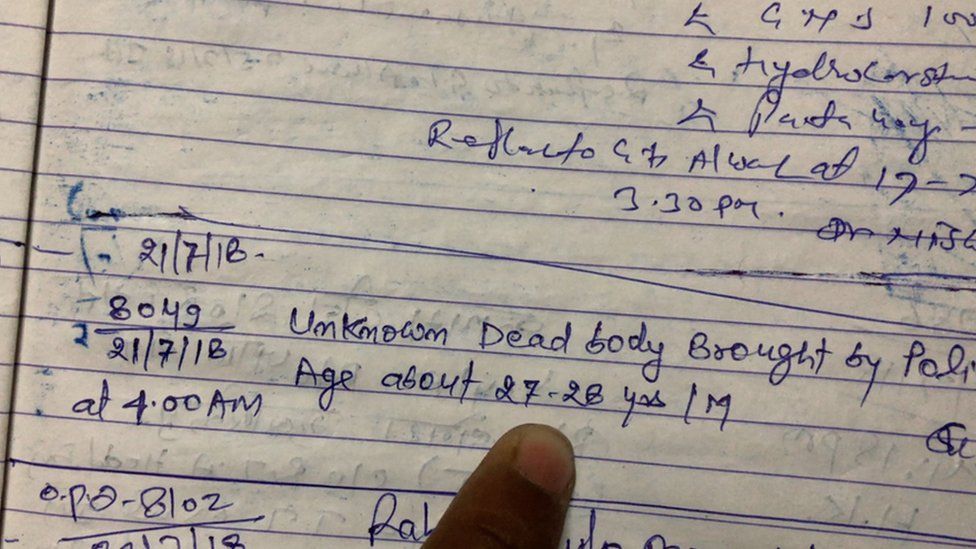

I go to the hospital in Ramgarh, where Rakbar was taken. Hospital staff are busily going through bound books of hospital records - looking for Rakbar's admission entry.

And then, there it is. "Unknown dead body" brought in at 04:00 on 21 July 2018.

For a start, Rakbar was found about 12 minutes' drive away from the hospital. Why did it take more than three hours for them to take him there?

And if the police say Rakbar gave them his name, why did they tell the hospital they didn't know who he was?

Nawal Kishore Sharma claims to know why. He paints a very different picture of what happened to Rakbar.

He tells me that after picking up Rakbar, they changed his clothes.

He then claims to have taken two photos of Rakbar - who at this point was with the police.

"The police injured him badly. They even beat him with their shoes," he says.

"They kicked him powerfully on the left side of his body four times. Then they beat him with sticks. They beat him here (pointing at his ribs) and even on his neck."

At about 03:00 Nawal Kishore Sharma says he went with some police officers to take the two cows to a local cow shelter. When he returned, he says, the police told him that Rakbar had died.

Rakbar's death certificate shows that his leg and hand had been broken. He'd been badly beaten and had broken his ribs, which had punctured his lungs.

According to his death certificate he died of "shock… as a result of injuries sustained over body".

I ask the duty doctor at the hospital whether he remembers what Rakbar's body was like when the police brought it in.

"It was cold," he says.

I ask him how long it would take for a body to become cold after death.

"A couple of hours," he replies.

Since Rakbar's murder several police officers have been suspended. I want to know why.

He looks uneasily at me.

"There were lapses on the police side," he says.

I ask him what those lapses were.

"They had not followed the regular police procedure, which they were supposed to do," he says. "It was one big lapse."

Three men from Nawal Kishore Sharma's vigilante group have been charged with Rakbar's murder. Sharma himself remains under investigation.

The vigilante group and the police blame each other for Rakbar's death, but neither denies working together that night.

The way Sharma describes it, the police cannot be everywhere, so the vigilantes help them out. But it's the police that "take all the action" he says.

Across the state there are dozens of formal cow checkpoints, where police stop vehicles looking for smugglers who are taking cows to be killed.

I visited one of the checkpoints. Sure enough police were patiently stopping vehicles and looking for cows.

The night before officers had had a gun battle with a group of men after a truck failed to stop.

These checkpoints have become common in some parts of India. Sometimes they are run by the police, sometimes by the vigilantes, and sometimes by both.

This gets to the heart of Rakbar's case.

Human rights groups argue that his murder - and others like his - show that in some areas the police have got too close to the gangs.

In some areas, police have been reluctant to arrest the perpetrators of violence - and much faster to prosecute people accused of either consuming or trading in beef, he says.

Human Rights Watch has looked into 12 cases where it claims police have been complicit in the death of a suspected cow smuggler or have covered it up. Rakbar's is one of them.

But this case doesn't just illustrate police failings. Some would argue that it also illustrates how parts of the governing BJP party have inflamed the problem.

Gyandev Ahuja is a larger-than-life character. As the local member of parliament in Ramgarh at the time when Rakbar was killed he's an important local figure.

He has also made a series of controversial statements about "cow smugglers".

After a man was badly beaten in December 2017 Ahuja told local media: "To be straightforward, I will say that if anyone is indulging in cow smuggling, then this is how you will die."

After Rakbar's death he said that cow smuggling was worse than terrorism.

One of Prime Minister Narendra Modi's ministers was even photographed garlanding the accused murderers in a cow vigilante case. He has since apologised.

Meenakshi Ganguly of Human Rights Watch says it is "terrifying" that elected officials have defended attackers.

"It is really, at this point of time, something that is a great concern, because it is changing a belief into a political narrative, and a violent one," he says.

The worry is that supportive messages from some of the governing party's politicians have emboldened the vigilantes.

No official figures are kept on cow violence, but the data collected by IndiaSpend suggests that it started ramping up in 2015, the year after Narendra Modi was elected.

IndiaSpend says that since then there have been 250 injuries and 46 deaths related to cow violence. This is likely to be an underestimate because farmers who have been beaten may be afraid to go to the police - and when a body is found it may not be clear what spurred the attack. The vast majority of the victims are Muslims.

"To say the BJP is responsible is perverse, inaccurate and absolutely false," he tells me.

"Many people have an interest in building a statement that the BJP is behind it. We won't tolerate it."

I ask him about Gyandev Ahuja's inflammatory statements.

"Firstly that is not the party's point of view and we have very clearly and unequivocally always said an individual's point of view is theirs, the point of view of the party is articulated by the party.

"Has the BJP promoted him or protected him? No."

But a month after this interview, Ahuja was made vice-president of the party in Rajasthan.

Shortly afterwards, Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Rajasthan - publicly slapping Ahuja on the back and waving together at crowds of BJP supporters.

"Show me how you raise seven children without a husband. How will I be able to raise them?" she says, wiping away tears.

"My youngest daughter says that my father went to God. If you ask her, 'How did he go to God?' she says, 'My father was bringing a cow and people killed him.'

"The life of an animal is so important but that of a human is not."

The trial of the three men accused of his murder has yet to take place, but perhaps we will never know what really happened to Rakbar.

In November 2015, photographer Allison Joyce spent a night following Nawal Kishore Sharma's vigilantes in the countryside near Ramgarh. One of her photographs shows a police officer embracing Sharma after a shootout between the vigilantes and a suspected cow smuggler.

Though the police now accuse the cow vigilantes of killing Rakbar Khan, and the vigilantes accuse the police, the photograph illustrates just how closely they worked together.

There are also claims that the police stopped and drank tea instead of taking Rakbar to hospital.

Whatever they did, they did not take Rakbar to hospital immediately.

No comments:

Post a Comment